How to stop the onion denial (of service)

[Post originally appeared on the Tor blog]

As you might have heard, some onion services have been experiencing issues with denial-of-service (DoS) attacks over the past few years.

The attacks exploit the inherent asymmetric nature of the onion service rendezvous protocol, and that makes it a hard problem to defend against. During the rendezvous protocol, an evil client can send a small message to the service while the service has to do lots of expensive work to react to it. This asymmetry opens the protocol to DoS attacks, and the anonymous nature of our network makes it extremely challenging to filter the good clients from the bad.

For the past two years, we’ve been providing more scaling options to onion service operators, supporting more agile circuit management and protecting the network and the service host from CPU exhaustion. While these don’t fix the root problem, they provide a framework to onion service operators to build their own DoS detection and handling infrastructure.

Even though the toolbox of available defenses for onion service operators has grown, the threat of DoS attacks still looms large. And while there is still a bunch of smaller-scale improvements that could be done, we believe that this is not the kind of problem that a parameter tweak or small code change will make it disappear. The inherent nature of the problem makes us believe that we need to make fundamental changes to address it.

In this post, we would like to present you with two options that we believe can provide a long-term defense to the problem while maintaining the usability and security of onion services.

The intuition to keep in mind when considering these designs is that we need to be able to offer different notions of fairness. In today’s onion services, each connection request is indistinguishable from all the other requests (it’s an anonymity system after all), so the only available fairness strategy is to treat each request equally – which means that somebody who makes more requests will inherently get more attention. The alternatives we describe here use two principles to change the balance: (1) the client should have the option to include some new information in its request, which the onion service can use to more intelligently prioritize which requests it answers; and (2) rather than a static requirement in place at all times, we should let onion services scale the defenses based on current load, with the default being to answer everything.

Defenses based on anonymous tokens

Anonymous tokens are hot lately, and they fit Tor like a glove. You can think of anonymous tokens as tickets, or passes that are rewarded to good clients. In this particular context, we could use anonymous tokens as a way to prioritize good clients over malicious clients when a denial of service attack is happening.

A major question here is how good clients can acquire such tokens. Typically, token distribution happens using a scarce resource that a DoS attacker does not have ample: CAPTCHAs, money, phone numbers, IP addresses, goodwill. Of course, the anonymous nature of our network limits our options here. Also, in the context of the DoS problem, it’s not a huge deal if an evil client acquires some tokens, but it’s important that they are not able to acquire enough tokens to sustain a DoS attack.

One reasonable approach for bootstrapping a token system is to setup a CAPTCHA server (perhaps using hCaptcha) that rewards users with blinded tokens. Alternatively, the onion service itself can reward trusted users with tokens that can later be used to regain access. We can also give users tokens with every donation to the Tor Project. There are many different types of tokens we can use and different user workflows that we can support. We have lots of ideas on how these tokens can interact with each other, what additional benefits they can provide, and how the “wallets” could look (including Tor Browser integration).

An additional benefit of a token-based approach is that it opens up a great variety of use cases for Tor in the future. For example, in the future tokens could be used to restrict malicious usage of Tor exit nodes by spam and automated tools hence reducing exit node censorship by centralized services. Tokens can also be used to register human-memorable names for onion services. They can also be used to acquire private bridges and exit nodes for additional security. Lots of details need to be ironed out, but anonymous tokens seem like a great fit for our future work.

In terms of cryptography, anonymous tokens at their basic form are a type of anonymous credential and use similar technology and UX to PrivacyPass. However, we can’t use PrivacyPass as is, because we want to be able to have one party issue tokens while another party verifies them – a functionality not currently supported by PrivacyPass. For example, we want to be able to setup a token issuing server on some separate or independent website, and still have onion services (or their introduction points) be able to verify the tokens issued by that server.

Of course, when most tech people hear the word “token” in 2020, their mind directly skips to blockchains. While we are definitely monitoring the blockchain space with great interest, we are also cautious about picking a blockchain solution. In particular, given the private nature of Tor, it’s hard finding a blockchain that satisfies our privacy requirements and still provides us with the flexiblity required to achieve all our future goals. We remain hopeful.

Defenses based on Proof-of-Work

Another approach to solving the DoS problem is using a Proof-Of-Work system to reduce the computational asymmetry gap between the service and the attacker.

Another approach to solving the DoS problem is using a Proof-Of-Work system to reduce the computational asymmetry gap between the service and the attacker.

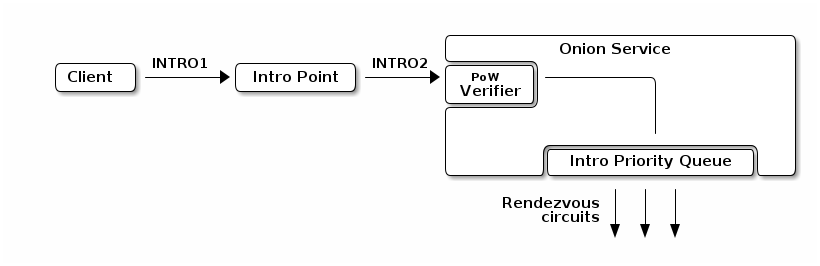

In particular, onion services can ask the client to solve a Proof-of-Work puzzle before allowing entry. With the right Proof-of-Work algorithm and puzzle difficulty, this can make it impossible for an attacker to overwhelm the service, while still making it reachable by normal clients with only a small delay. Similar designs have also been proposed for TLS.

We have already started writing a proposal for this system (with the great help of friends and volunteers) and we are reasonably confident that existing proof-of-work algorithms can fit our use case while providing the right level of protection. Given the complexity of the system there is still work to be done on the parameter tuning as well as on tuning the Tor introduction scheduler, but initial analysis seems very fruitful.

The great benefit of this approach is that the proposed PoW system is dynamic and automatically adapts its difficulty based on the volume of malicious activity that is hitting the service. Hence, when there is a big attack wave the difficulty increases, but it also scales down automatically when the wave has passed. Furthermore, if we pick a proof-of-work system where doing more work creates a better proof, motivated clients can “bid” for attention by spending time to create an extra-good proof, which would let the onion service prioritize it over the other requests. This approach turns the asymmetry to our advantage: good clients make a small number of connections and they need a way to stand out amid an attacker pretending to be many clients.

Conclusion

We believe that the above two schemes provide a concrete framework that will strengthen the resilience of onion services in a fundamental way.

Both proposals can be applied together and they are complementary to each other. It’s worth pointing out that both proposals are technically and cryptographically heavy and have their own drawbacks and limitations. Nobody wants a Tor network full of CAPTCHAs or mobile-prohibiting PoW puzzles. Parameter tuning and careful design is vital here. After all, DoS-resilience is a game of economics: the goal is not to be perfect; the goal is to raise the bar enough so that the attacker’s financial cost of maintaining an attack is higher than the gain. Or said another way, the steady-state we want to reach is that you typically don’t need to present a captcha or token to visit an onion service, and the reason is that nobody is attacking them because the attacks don’t work.

We hope that our post inspired you to think about our ideas and come up with your own attacks and improvements. This is not a problem we can solve over a day, and we appreciate all the research and help we can get. Please get in touch!